Learning and Unlearning Community Engagement

When a project impacts the quality of life of a particular community, the designer, client, and stakeholders are each responsible for the outcome. A community is defined by the size, complexity and histories of a group of people connected by a common interest. The broad topic of “community engagement” is constantly changing in pedagogy. Carducci Associates continually investigates forms of engagement to ensure positive outcomes for public and community-focused projects. As fellow coworker Wesley Bexton states, the best approach to all our community outreach experiences is grounded in honesty, humility, and compassion.

During nearly two years of work at Carducci Associates, I have experienced several scales of design and planning community engagement processes. Whether we’re discussing a small neighborhood park or a school campus, my observations are grounded in my involvement in activism as a student.

Unlearning is a process that identifies outdated, restrictive models and replaces them with improved, more inclusive practices. Unlearning requires the perseverance to reflect on knowledge, skills, and outcomes of previous models. Our current model emphasizes the designer’s role as facilitator. The physical layout of a meeting is a good example of nurturing the unlearning process: the designer shifts from leading at the front of the room, to facilitating as one among a circle of participants, where both can feel more comfortable speaking and listening to each other.

Through my education, I have defined guidelines to foster a safe and productive space for decision-making tailored to the community involved in a specific project:

- A positive outcome depends on preparation; in advance, the facilitator drafts an agenda.

- At the meeting, the facilitator sets objectives for the discussion while clarifying their role as listener as opposed to leader of the conversation.

- The facilitator should be aware of participant’s goals as much as their own. Begin the meeting with each attendee sharing a brief introduction and goal for the meeting to create a shared language of diverse perspectives.

- Throughout the meeting, the facilitator listens to and documents all suggestions and concerns and provides honest responses where needed to assure no false promises or hopes.

The following experiences at Carducci have inspired new strategies for a more effective approach to community and stakeholder meetings.

Le Conte Elementary School, Berkeley

As experienced by Associate Principal Wesley at LeConte Elementary School, a site committee led the development of a landscape master plan and a resulting capital improvement projects for immediate development. During the final meeting of the site committee prior to board approval, a large group of parents in attendance communicated they had only just learned of the planning process, and had missed the opportunity to participate. This group had previously conducted an independent study that would have informed the master plan’s development, which in turn would have led to different development priorities.

“We needed to find a way in that meeting to unlearn, with our site committee, the process we had assumed would occur,” Wesley states, “and as a group expand the discussion to include these additional community members in a way that respected the work already accomplished by the site committee, and equally respect the points of view held by the independent group. We spoke to district decision makers who agreed to extend the community process so that the additional input could be incorporated, and were able to schedule several more meetings to address the expanded discussion in a meaningful way.

We created a community input process that allowed us to visualize critical issues for the campus through the lens of both the staff and the students in a way that was immediately apparent and accessible to the group. We correlated the data gathered by the independent group with the data we’d gathered through our own process, and demonstrated the correlation to our expanded group. The additional input didn’t ultimately change the master plan itself, but dramatically changed key priorities, which led to a very different capital improvement scope that addressed needs identified by both students and the independent group.”

Washington and Rosa Parks Elementary Schools, Berkeley

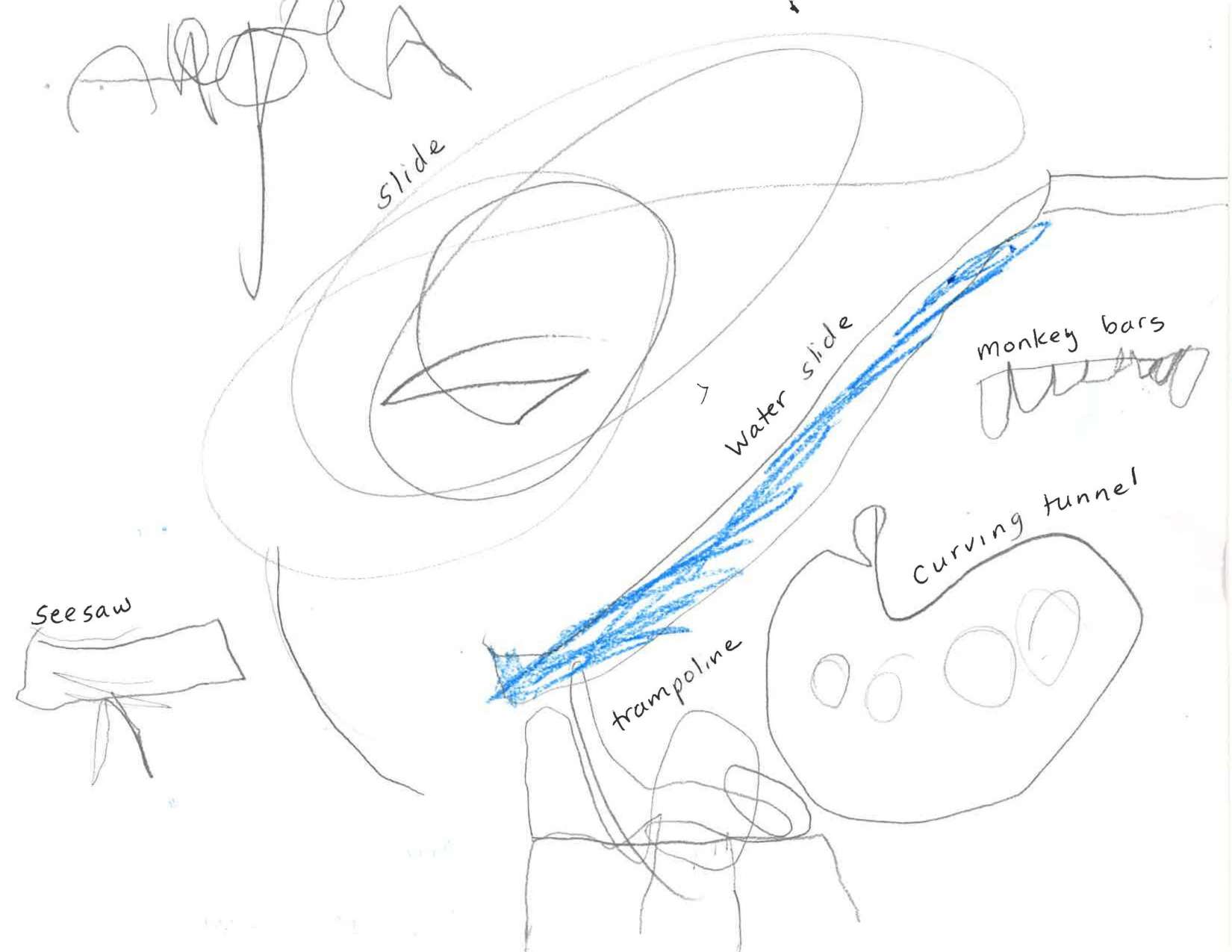

For Washington and Rosa Parks Elementary Schools, Wesley and I applied lessons learned from the LeConte community meetings. While flexibility and redirecting decision-making are very important skills, using media that communicates across different user groups is vital to retrieve genuine feedback. We used the community input process created for LeConte to generate feedback from both staff, and students. This process asks basic questions that can be answered simply or in narrative form and asks participants to map out their ideal campus plan, as well as identify specific “problem areas” on the site. We interpret the narrative usually to make it accessible to the site committee; and additionally graphically represent concepts and issues identified on the campus maps onto a plan that usually weights each concept – a word map – to help guide the decision-making process. This input process generates what was called by an architect on one committee, “the most democratic design process [he’d] encountered.” The exploration of playground program informs the master plans and the capital improvements prioritized for that summer. In the end, the input gathered, highlighted student needs that led our site committee to critical discussions re-envisioning campus program, and distilled a campus design favorable to all stakeholders. This project not only changed the structure and breath of play experiences for the students, but also increased the quality of interactions with students for the teachers and staff both on the school yard and in the classroom.

John Hinkel Park, Berkeley

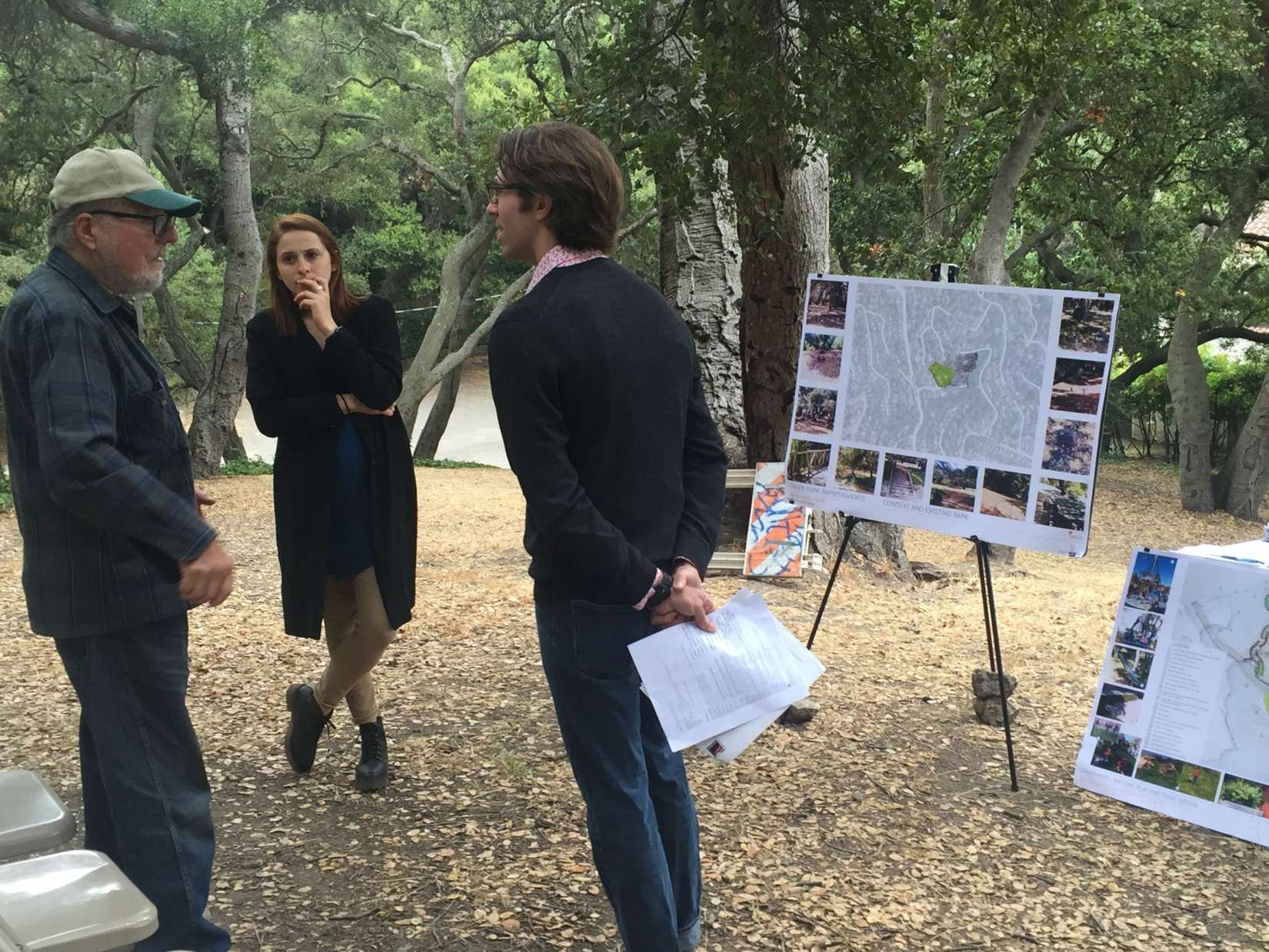

Researching the stakeholders connected to this park - neighbors, parents and children – as well as the structures regulating the park – a historic landmark title – improved our preparation for these community meetings. As a result, we were able to create goals for the project aligned with a number of competing values held by stakeholders.

Hosting the community meeting at the site allowed us to address barriers in both design process and topography. Upon seeing the meeting in process, park neighbors, including contractors and designers, joined the project. Because a key site challenge was its steep topography, participants unaccustomed to contour maps could walk the site with us, locate places simultaneously on the plan drawings and in the park, and come to a better understanding of design decisions.

As this process continues today, it is clear that extracting information from the park’s users about their needs allows for us as designers to communicate to the client the possibilities of engagement. The relationship between the client, stakeholders and designers allows for inspiring interactions yielding designs that increase impact and reduce inefficiencies.

City Parks and Recreation Today

A foundation of trust with stakeholders goes hand-in-hand with a productive and valuable community engagement process. The knowledge and skills invested by the community in the design process inspires exciting outcomes and experiences for the end user. At a recent interview for an East Bay landscape architect on-call position, we encountered reminders of language barriers and political climate. By hiring a Spanish-speaking staff member in their Parks and Recreation Department, the city noted an increase in engagement from Spanish-speaking community members in parks and recreational issues. Building trust through listening and fostering an accessible and safe environment better ensures that public facilities serve the entire community. Our learning and unlearning of engagement practices is fluid, to meet the needs of the community and create stronger partnerships.

Karly Behncke and Wesley Bexton, your neighborhood designers

Edited by Petra Marar

Community Meeting